First published on NorskFisk.no on December 22nd 2022, i spalten Frode Blakstad tar ordet.

INAQ AS has conducted operational reviews of numerous land-based projects in recent years. Additionally, we have been responsible for developing business plans for similar projects. We have assembled interdisciplinary teams comprising personnel with expertise in biology, technology, and economics.

Based on our experiences, I have sought assistance from senior advisors Onno Musch and Roger Oddebug to author this article, which focuses on the current status of RAS facilities.

Oppdrett i RAS-anlegg

There has been significant development in new projects for land-based salmon farming, occurring across multiple dimensions. The focus has been on technology for producing larger smolt and large-scale food fish production on land.

Several facilities are currently being sized for large smolt and post-smolt production. The ambition is to produce fish ranging from 300 grams up to 1 kilogram. The average size of smolt is increasing, and some producers have achieved stable production of smolt at approximately 300-350 grams. There are also several pilot plants and small-scale operators producing land-based salmon up to 5 kilograms, along with a handful of actors who have progressed significantly with the construction and startup of larger intensive facilities for land-based food fish farming.

However, it must be noted that so far, no facility has achieved stable and profitable large-scale land-based production of food fish salmon. We will discuss the primary reasons for this and how investors can value such facilities based on the current situation.

Challenges and Complexities

Land-based facilities for salmon farming with recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) are highly complex structures. Several aspects are individually demanding and interconnected, meaning that problems in one dimension can lead to issues in other areas. These dimensions primarily include:

- Technical systems

- Biological processes

- Operational management

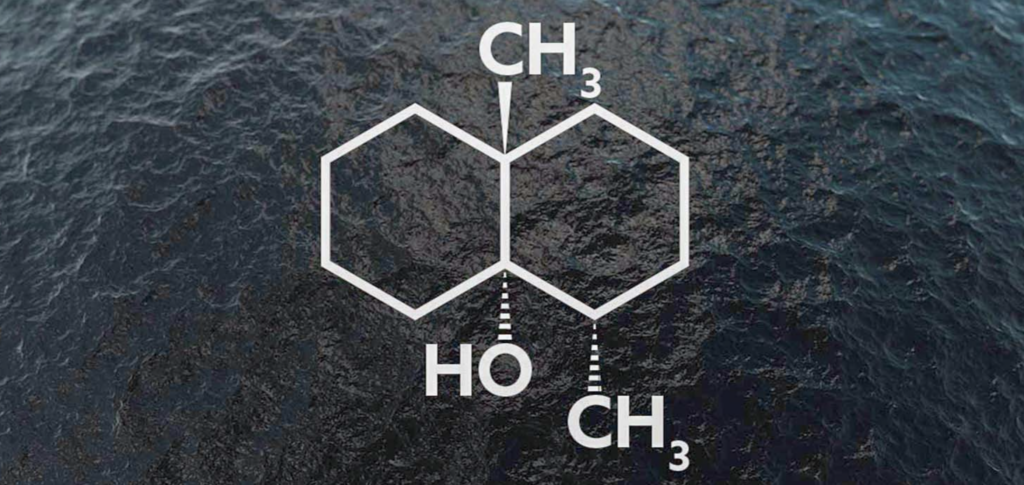

The technical systems include everything from water treatment systems, feeding systems, fish handling, sludge treatment, and biofilter technology. Many systems have limited maturity and few documented long-term operational results, particularly for larger fish. This is especially true for solutions unique to land-based food fish production, such as efficient and gentle handling of large fish and systems for removing Geosmin (earthy taste in fish).

There are also significant biological challenges in land-based farming facilities, related both to internal processes within the facility (fish health and behavior) and the biology of the biofilter, as well as external influences like pathogen infiltration via water or air. Due to limited experience with land-based farming of larger fish, there remains a high degree of uncertainty and significant challenges, including early sexual maturation, consistent growth, and adequate cleaning routines for facilities in intensive and continuous operation. Additionally, unpredictable fish behavior can pose challenges for the systems to manage.

Due to limited experience with land-based farming of larger fish, there remains a high degree of uncertainty and significant challenges, including early sexual maturation, consistent growth, and adequate cleaning routines for facilities in intensive and continuous operation.

Operational management involves human competence, experience, and capacity to run such facilities. Few have extensive experience operating intensive land-based RAS facilities, and staffing new facilities presents major challenges. There is a high risk of human errors during the startup phase of new facilities while the team gains experience in operating the facility.

Risk and Incident Management

The range of undesired situations in RAS facilities can vary from slightly reduced growth or delayed milestones to incidents of mass mortality and loss of entire production cycles. Technical incidents like pump failures, filter blockages, or power outages can typically be managed if considered during the planning and construction phases. Measures such as varying degrees of redundancy and emergency supply solutions for all critical equipment can help mitigate risk. However, areas where low maturity can lead to suboptimal operations and reduced growth in the systems remain.

When biological and technological challenges are interconnected, unpredictable fish behavior might overload systems, or suboptimal design of tanks and operational equipment could injure fish, leading to reduced health. Pathogen entry into the facility can be especially challenging to eliminate, potentially requiring full disinfection of all systems, including the biofilter, resulting in prolonged operational downtime. Including a «seeding tank» to accelerate biofilter maturation during a restart can significantly reduce downtime.

Developing clear Standard Operating Procedures for regular operations and all possible emergency situations is another measure to reduce risk. Additionally, a strong emphasis on a comprehensive training phase, with practical experience transfer from operating similar facilities, is crucial.

Most larger facilities today have encountered incidents related to one or a combination of the mentioned challenges during the startup and ramp-up phases. Consequently, it is not uncommon for land-based facilities to produce well below planned capacity during the initial phase, sometimes as low as 50–60 percent of theoretical capacity.

Most larger facilities today have encountered incidents related to one or a combination of the mentioned challenges during the startup and ramp-up phases.

Premium or Standard Prices

In addition to the risk elements associated with production itself, there is still considerable uncertainty regarding the market for land-based farmed fish. While business plans for land-based production facilities often assume premium prices for their products based on a history of good environmental conditions, fish health, and documentable quality without external influences and the need for antibiotics, it is still too early to say how consumers will react to this product segment. High quality and good taste experience will be crucial for achieving a good market price. A prerequisite for this will be the implementation and adherence to good quality systems.

Valuation and Market Considerations

Valuing land-based aquaculture facilities is challenging due to few comparable projects and high-risk profiles. However, qualified valuations are necessary for investments, acquisitions, and other transactions.

Potential valuation methods include market-based valuation (MBV), balance-based valuation (BBV), and earnings-based valuation (EBV).

MBV can provide a good estimate for mature market areas, but lacks comparable references for land-based food fish salmon. BBV focuses on asset value in case of resale and is less representative for production facility valuation, serving primarily as a reference against alternative construction projects elsewhere. EBV can be a good approach by examining company-specific earnings expectations, though it requires independent sources to verify key assumptions such as prices and market trends.

The Discounted Cash Flow method (an EBV method) is preferred for valuing early-stage RAS projects if price estimates from management and suppliers are critically reviewed by a qualified third party. The assessment should also consider the most relevant and comparable industry references (MBV).

Apart from uncertainty surrounding price estimates, there are several risk factors associated with the valuation using the Discounted Cash Flow method for investments in RAS facilities. Delays and extensions in construction timelines will lead to longer periods of net expenditures, and additionally, there is a risk of underestimating the ramp-up period for production capacity. Such delays could significantly impact the valuation negatively for a potential investor. It is also challenging to stress-test business plans for significant cost overruns in construction projects, as well as major events like mass mortality and substantial deviations from planned production capacity. Moreover, evaluating the scope and need for working capital over extended periods is challenging. It takes approximately two years to produce a salmon, and significant capital is tied up in biomass before it can be sold.

We would recommend that investors thoroughly familiarize themselves with the various concepts available in the market.

High Return Requirements

Based on relatively high risk, low maturity, and other factors like illiquidity premiums and small business premiums, most investors set high return requirements. They have significant expectations for potential upside from such investments.

Investors in land-based aquaculture facilities currently expect returns of around 12–20%, depending on various investment conditions. With an average exit strategy based on a timeline of 5 to 7 years for a typical private equity investor, land-based aquaculture operators face high demands in achieving their goals to meet expectations.

INAQ’s advice to new investors in the RAS segment is to be aware that this is an industry in continuous development with relatively low maturity compared to traditional sea-based salmon farming. Therefore, one should anticipate some hiccups in the initial phase, and investors may need to be prepared to stay committed longer than usual.

Additionally, we would recommend that investors familiarize themselves thoroughly with the various concepts available in the market. This includes which species are better or worse suited for RAS farming, as well as strategic choices such as low energy consumption versus high growth rates, production near the market versus production in areas with natural advantages and access to local expertise, premium markets versus economies of scale, etc. In any case, it pays off to collaborate with qualified players possessing relevant experience in the industry.

Advice for Seafood Operators

INAQ’s advice to operators seeking investors for land-based food fish farming is to focus on competence and experience. Successful land-based aquaculture requires expertise in biology, technology, and operations. Fish are produced not in spreadsheets but through a complex interplay between facilities, water, fish, and people, where pathogens and other unwelcome guests can surprise. Experience in all project organization stages, including management and suppliers, reassures investors. Where experience is lacking, a clear competency strategy with experience transfer from similar facilities is essential. It is also recommended to consider whether the project would benefit from “competent” capital—investors who can contribute relevant expertise, though potentially more costly.

Our experience suggests that operators can positively differentiate themselves by demonstrating plans for robust quality systems and manuals, realistic plans for construction, startup, and, most importantly, ramp-up and production based on biological and fish welfare considerations.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Frode Blakstad (65) is a partner and working chairman at INAQ AS in Trondheim. He graduated as a food technologist from Statens Næringsmiddeltekniske Skole in 1982, obtained a college degree in economics from Trondheim Økonomiske Høgskole in 1985, and completed a Master of Management at BI in Oslo in 2005. From 1984 to 1988, he worked at the Norwegian Technological Institute. He was then the managing director at Akva lnstituttet AS until 1996 and a partner at KPMG Consulting until 2000.

Since 2000, he has been a partner, CEO (2000-2018), and working chairman (2018-) at INAQ AS. Blakstad holds several board positions, including chairman of Sekkingstad AS, Trient AS, Torghatten Aqua AS, and Peter Hepsø Rederi AS, and board member at Bjørøya AS.

He has been a regular guest writer in Norsk Fiskerinæring since 2017.