First published on NorskFisk.no on 31. March 31st, 2023

INAQ AS assists national and international players in the seafood industry in creating strategic plans tailored to anticipated market developments. Analyzing the downstream activities in the value chain of salmon provides a foundation for many valuable reflections and strategic choices. Based on our experiences and analyses of relevant data, I sought assistance from senior advisors Nina Santi and Jørn Pedersen to write this article, which focuses on: Where does the salmon go — will it find new paths in the future?

Many may have the impression that Norwegian salmon reaches all corners of the world and finds its way into billions of homes globally. But who actually receives the more than one million tonnes of salmon we export from Norway each year? Will an increasing focus on sustainability lead to changes in how Norwegian salmon reaches the markets?

Norwegian Salmon Goes to Europe

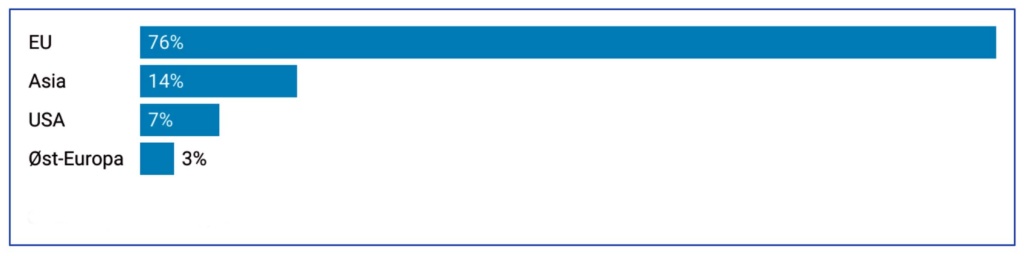

In 2022, Norway exported 1.25 million tonnes of salmon and salmon products measured in product weight. Figure 1 below shows some key statistics.

More than three-quarters of the salmon produced in Norway takes the quickest route down to Europe. Europe also receives salmon from the Faroe Islands, Scotland, Iceland, and even some from Chile. The EU is the world’s largest market for salmon, and it is notable that what constitutes about 5 percent of the world’s population receives more than 50 percent of all farmed salmon globally. A larger share of Norwegian salmon goes to the EU than ten years ago. In 2012, a total of 170,000 tonnes of Norwegian salmon went to Russia, but since the invasion of Crimea in 2014, Russia has no longer been a market for Norwegian salmon. It was mainly the EU that took over the volumes after the exports to Russia stopped.

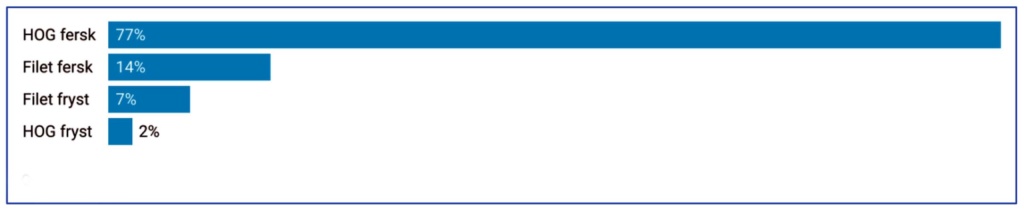

Most of the salmon leaves the country as fresh and minimally processed fish, meaning gutted only. See Figure 2 below. This snapshot of Norwegian salmon exports shows that the EU is the dominant market and whole, fresh salmon is the dominant product. In 2022, 90 percent of Norwegian salmon exports to the EU were whole, fresh salmon. The share of salmon exported as fillet has slightly increased over the past decade, reaching 16 percent in 2022 compared to 12 percent in 2014.

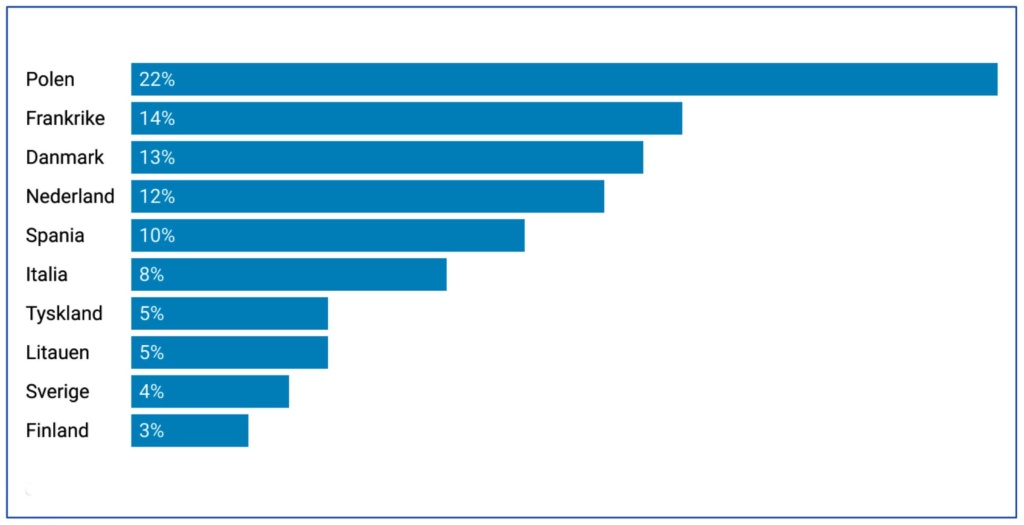

Most of the processing of Norwegian salmon thus takes place in Europe, with the volume distributed across various countries. This is evident from Figure 3. Among the EU countries, Poland is the largest importer of Norwegian salmon. Last year, about 22 percent of the volume went there.

Asia is a populous continent with strong traditions for seafood consumption. Asia is the second largest market for Norwegian salmon, and in 2022, 14 percent of Norwegian salmon went to this continent. Of the total volume to Asia, 42 percent was sold to Southeast Asian countries, 21 percent went to Japan, while the remaining countries in the region took 37 percent. In 2022, there was a decline in exports to both Japan and South Korea compared to the previous year, likely influenced by changes in air traffic due to the war in Ukraine. Thailand is a growing market, and here the Seafood Council has employed new marketing strategies by using professional influencers to reach new consumers.

The USA is the largest single market for salmon, taking about 15 percent of the global volume. Chile is the largest exporter of salmon to the USA, but salmon also comes from Canada, Norway, the Faroe Islands, and Scotland. Seven percent of Norwegian salmon production went to the USA in 2022. There appears to be significant potential to increase salmon consumption in the USA, where the average per capita consumption is 1.3 kilograms. There is considerable variation between European countries, but for comparison, the corresponding figure is over 2.4 kg per capita in the EU.

A market to watch in the future is the Middle East. Israel is the largest export market for salmon in the region. Norwegian salmon appears to be increasingly popular during the celebration of the Sabbath. Saudi Arabia has also increased its import of Norwegian salmon in recent years. The same can be said for Egypt, which also imports other Norwegian seafood. The Seafood Council is intensifying its efforts in the region, so more growth could be forthcoming here.

There is undoubtedly a significant untapped potential for the sale of Norwegian salmon to other parts of the world, not least to the USA.

Pandemic, War, High Inflation, and Climate Crisis

The early years of the 2020s have been eventful in many ways. Salmon, however, largely continues to follow established routes out of Norway. Most are still exported as whole fish in ice-packed crates and loaded onto trucks for the fastest route to Europe. The salmon market in Europe is evidently very adaptable even during drastic changes like those we have experienced in recent years, with both COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. There is undoubtedly a significant untapped potential for the sale of Norwegian salmon to other parts of the world, not least to the USA. It is therefore worth asking why so much of Norwegian salmon is shipped unprocessed by truck to Europe. Is it because it is the most comfortable for Norwegian salmon producers? Will this continue in the foreseeable future, or could the salmon market be influenced by other factors that lead to changes in product flows? We have looked at some development trends that may be interesting to consider moving forward.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the flow of goods and logistics worldwide. Airfreight and shipping prices soared as the world shut down. While prices on marine traffic routes have normalized after the pandemic, air transport remains at a high level compared to pre-2020. In the past year, the war in Ukraine has led to longer transport routes for many destinations. In Europe, the war has resulted in sky-high energy prices and strong inflation in food prices. Over time, this development may weaken purchasing power and demand for salmon in Europe. According to some actors, this has already affected the market. At the same time, salmon prices continue to remain high and have set several new records in recent weeks. This may be an effect of increasing demand from new markets. Will Norwegian producers and exporters consider market opportunities outside Europe to a greater extent in the future?

There are many reasons why salmon leaves Norway whole and minimally processed. In the case of the EU, tariffs increase with the degree of processing, so, for example, there is a 2 percent tariff on whole salmon and salmon fillet, while there is a 13 percent tariff on smoked salmon from Norway to the EU. Another factor is the price of labor, which makes Norway less competitive in processing. The high cost of labor, however, has served as an incentive to develop automated solutions. Slaughterhouses in Norway have become larger and more automated, leading to strong consolidation on the slaughter side in Norway over the last decades. Most of the approximately 45 remaining salmon slaughterhouses are integrated into larger aquaculture companies or have a consortium of producers on the ownership side.

For Norwegian salmon to the USA, a reception system is not in place to handle the further processing of salmon to the same extent as in the EU. Norwegian salmon to the USA is therefore primarily further processed to fillet or portion pieces. The capacity for filleting is limited in Norway, and this currently limits the volume of direct fillet exports to the USA. Some Norwegian players, however, are working purposefully towards the American market, and as part of this, they are expanding filleting capacity. Examples of this are the aquaculture companies Hofseth and Kvarøy. However, there are also further processing companies in the EU that export Norwegian salmon fillets to the USA.

Japan and South Korea are two consistently good salmon markets, where salmon is a central ingredient in sushi and sashimi. Norway is the main supplier of salmon to both countries. While it has been common in South Korea to import whole salmon for further processing into fillets locally, we now see a shift towards a higher fillet share. For Japan, already 70 percent of the salmon is imported as fillet. Growth towards Asian markets will likely also involve a trend towards more processed products.

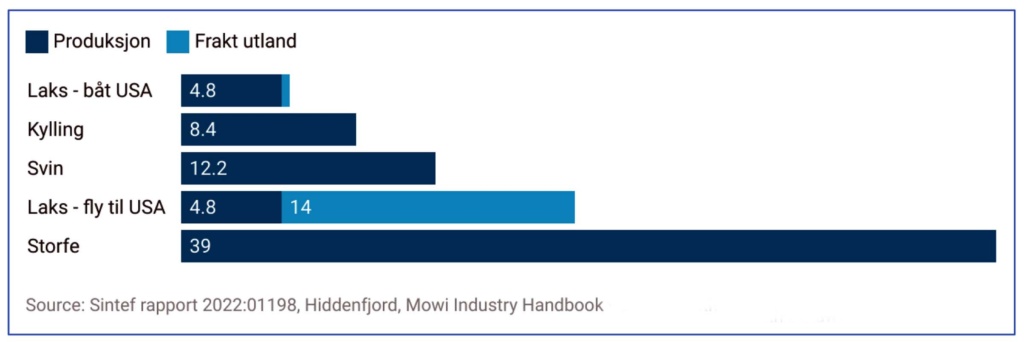

Asian markets prefer fresh salmon, and salmon is transported by air. Norwegian salmon to the USA also goes by air with high transport costs and a significant carbon footprint. If more salmon is to go to more distant markets, the economic and ecological costs associated with transportation increase. Global food systems account for more than a third of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly common and important to calculate the carbon footprint of food products, and efforts to reduce the carbon footprint in food production will over time also affect the flow of salmon products. The sustainability perspective will become more important for all actors involved in the production and distribution of salmon. Both the product, the route, and the mode of transport to the market significantly impact the carbon footprint of salmon. Compared to land-based animals, which are mainly produced near consumers and therefore transported over short distances, this must be taken into account.

Japan and South Korea are two consistently good salmon markets, where salmon is a central ingredient in sushi and sashimi. Norway is the main supplier of salmon to both countries.

SINTEF recently released an updated report on the carbon footprint of Norwegian salmon (SINTEF Report 2022: 01198). The most carbon-friendly transportation methods are by train or ship, while air transport performs very poorly. According to the SINTEF report, air-transported salmon to Asia or the USA results in carbon emissions of 16–28 kg CO2 equivalents per kilo of edible product at delivery to the distributor. Here, air freight accounts for 68–82% of the salmon’s carbon footprint before it reaches the market. In comparison, transport accounts for about 10% of the carbon footprint for truck transport to the European market. The climate footprint is only marginally higher for frozen salmon shipped to Asia than for fresh salmon transported by truck to the EU. See Figure 4.

The Norwegian seafood industry has, and must have, significant sustainability ambitions. One consequence will be that the industry will need to look for alternatives to air-transported salmon to the USA and Asia. The organization Future in Our Hands pointed out in its 2018 report «The Pink Climate Bluff — Can a Sustainable Salmon Fly to China?» that the industry must take structural measures to reduce climate emissions. The Faroese producer Hiddenfjord has set an example by completely stopping air freight of salmon, a measure the company actively uses in marketing and profiling. With the low climate footprint of salmon transported by ship, this could be a way to meet the competition from land-based farming production near markets.

More fillet from Norway?

Delivering more processed products will help reduce the volume transported. However, the effect of this on the carbon footprint depends on equally good utilization of by-products in Norway as in the receiving country. In many receiving countries, there are good traditions for utilizing heads, belly flaps, backbones, and trimmings in fish food production. Norwegian processing companies have increasingly recognized the value of salmon by-products, which can also contribute to increased motivation for further processing.

Frozen salmon can be transported more efficiently compared to fresh salmon, as it avoids the need to transport ice along with the fish, and frozen salmon does not have the same urgency as fresh.

Frozen salmon can be transported more efficiently compared to fresh salmon, as it avoids the need to transport ice along with the fish, and frozen salmon does not have the same urgency as fresh. Fresh salmon is transported in polystyrene boxes with 20 kilos of salmon and five kilos of ice, while frozen salmon can be packed more efficiently and environmentally friendly in cardboard boxes weighing 2 kilos and holding 25 kilos of salmon, often fillets. Frozen salmon solves many challenges concerning the cold chain, logistics, and product shelf life. While fresh salmon has a shelf life of up to two weeks, frozen salmon can maintain quality for up to two years. Frozen whole salmon is a sought-after product for smokers because it makes them less affected by price fluctuations and ensures a steady supply of raw materials and good utilization of production capacity. For other applications, fresh salmon has both objective and perceived advantages compared to frozen salmon, and there is a greater need to convince consumers if one wants a shift from fresh to frozen salmon.

In many calculations, frozen fillets sent by boat will have the smallest climate footprint. Challenges with sending frozen fillets are mainly related to product quality. There have been developments in technology for freezing and thawing salmon, making it possible to better preserve product quality.

After slaughter, salmon is filleted either before (pre-rigor) or after (post-rigor) the onset of rigor mortis. It is difficult to mechanically fillet fish in rigor, as it gets a curved shape that is hard to process through a filleting machine. Additionally, the muscle is firm, making it hard to remove bones. Therefore, it is most common to produce post-rigor fillets 3-5 days after slaughter. This waiting period can just as well be spent in transport to the receiving country, which then handles the filleting. This is the case for salmon transported by truck to Europe.

Pre-rigor fillet is produced before rigor mortis sets in while the flesh is firm and pliable, making it easy to handle mechanically. These products reach consumers faster and have a longer shelf life as fresh products. Pre-rigor products frozen directly can also maintain very high quality if thawed correctly. Therefore, there is potential to develop supply chains where products are delivered with a combination of high quality and long shelf life by producing pre-rigor frozen fillet. These must then be delivered to professional actors who can perform the thawing in a way that preserves product quality. One advantage for the retail trade is that it can offer products equivalent to fresh ones, but it is easier to avoid food waste by adjusting supply to demand.

In the retail sector, there are also ongoing structural changes in the salmon’s receiving countries. Several large supermarket chains in the UK have closed their fresh fish counters. They have concluded that these are no longer an important factor in attracting customers. Consumers still choose seafood, but a good selection of fresh consumer packages has replaced seafood counters in many countries. This trend is likely to continue spreading.

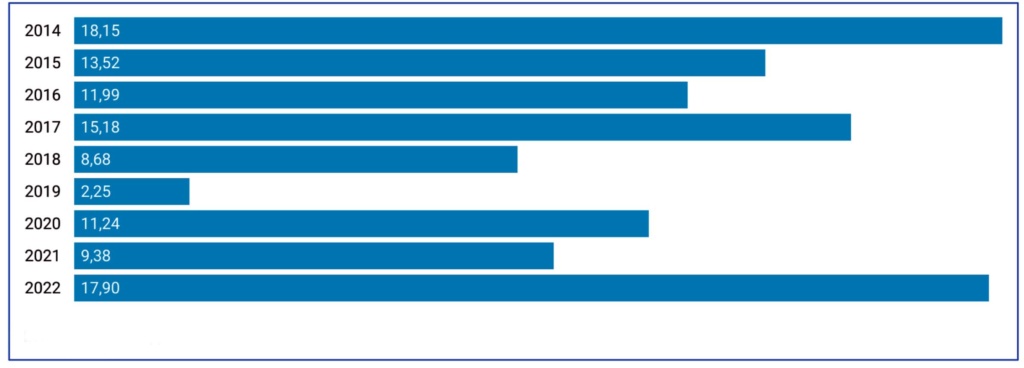

In this article, we have looked a bit closer at the price difference between fresh and frozen fillet. From 2014 to 2022, it has favored frozen fillet, with a significant price premium for frozen at times. Additionally, it is worth noting that the volume of frozen fillet to the USA has doubled from 2017 to 2022. See Figure 5.

Markets in Europe and the rest of the world have traditionally had, and still have, a clear preference for fresh products, and frozen salmon has a sort of second-rate reputation. There are many good reasons why an increasing share of Norwegian salmon should be filleted and frozen before export, but it requires acceptance from buyers and that supply chains are set up for this. However, not many consumers have had the opportunity to try properly thawed pre-rigor frozen fillet, as supply chains for such products almost do not exist. It will be interesting to see if Norwegian producers will give the world the chance to discover and accept that frozen fillet from Norway provides equally good end products and food experiences as salmon that has traveled from Norway with many kilos of ice and with head and backbone intact.

Norwegian salmon producers must prepare for a future where sustainability will be assessed not just based on production alone, but on the entire food system the product comes from. Food waste due to limited shelf life results in a loss of value from salmon production, and air freight significantly increases climate costs from producer to consumer. These are examples of factors that Norwegian producers can influence through their choices for the further development of the food systems around salmon.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Frode Blakstad (65) is a partner and working chairman at INAQ AS in Trondheim. He graduated as a food technologist from Statens Næringsmiddeltekniske Skole in 1982, obtained a college degree in economics from Trondheim Økonomiske Høgskole in 1985, and completed a Master of Management at BI in Oslo in 2005. From 1984 to 1988, he worked at the Norwegian Technological Institute. He was then the managing director at Akva lnstituttet AS until 1996 and a partner at KPMG Consulting until 2000.

Since 2000, he has been a partner, CEO (2000-2018), and working chairman (2018-) at INAQ AS. Blakstad holds several board positions, including chairman of Sekkingstad AS, Trient AS, Torghatten Aqua AS, and Peter Hepsø Rederi AS, and board member at Bjørøya AS.

He has been a regular guest writer in Norsk Fiskerinæring since 2017.